The cost of being a carer

In reading this article you will understand:

- Why it is in our interests to help unpaid carers get the support they need.

- What the results of increasing your caring responsibilities might be

- What percentage of carers are living in poverty

- The benefits available for carers.

Caring for family, friends or neighbours who are ill, disabled or elderly is something people do because they care in an emotional sense. But according to the NHS it takes, on average, two years for people to realise they are carers. This happens because they don’t tend to separate the practical help they provide from the relationship they have with that person.

The charity Carers UK says there are around 6.5 million unpaid adult carers in the UK, who collectively save the economy £132 billion a year. It is in all our interests to help unpaid carers get the support they need, as without them, our NHS and social care systems would be under even more pressure than they already are. But before we can better support carers, we need to understand who they are.

Building a picture

According to the DWP’s Family Resources Survey, published in March, people age 45 to 64 are most likely to be carers – although plenty are older or younger. Parents are most often the recipients of care – the survey shows that in the 2020-21 financial year, 34% of carers cared for a parent they didn’t live with and 4% cared for a parent in the same household.

Around 17% cared for a spouse or civil partner and a further 3% cared for a cohabitee, while 15% cared for a son or daughter. Caring for people who aren’t relatives is less common, but still a reality for the 6% caring for non-relatives such as friends and neighbours. Some people find themselves caring for more than one person, which amplifies the issues that any carer faces as they juggle their own lives with their caring responsibilities.

Carers often describe their role as rewarding, but it can be tough personally and financially. Their caring responsibilities might increase, resulting in stress, less time to work and less money, which can affect their ability to do the things they do to unwind. The financial impact of working less or giving up work altogether can be exacerbated by the cost-of-living crisis and the extra costs that come with caring for disabled or vulnerable people.

For example, the recipients of care may need to be accompanied to regular hospital appointments, leading to increased travel costs. They may have special dietary requirements or need electrical equipment at home to maintain their health, which increases energy use and adds to living costs.

Relative poverty

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation 2022 Poverty Report estimates that around 24% of carers in the UK were living in relative poverty in 2000/21. Carers who spend more time caring have higher poverty rates: 44% of working-age adults caring for more than 35 hours a week are in poverty compared to 17% caring for fewer than 20 hours a week.

Advisers will be well aware of the link between financial health and both physical and mental well-being. If carers are struggling financially, they may deny themselves simple pleasures in life, like hobbies, to save money. It may even be that they don’t have the time or the energy to focus on themselves, which can impact their own health and ultimately their ability to continue their caring responsibilities.

Local councils can provide practical help to give carers a break if carers ask for a carer’s assessment. The assessment may also lead to some financial help through a Carer Personal Budget – a lump sum designed to cover the next 12 months. However, local councils are also feeling the pressure on their budgets, so carers may turn to charities that support carers.

These charities often have case studies that tell carers’ stories in their own words. One of these case studies from Carers Trust – ‘Amanda’s story’ – perfectly sums up carers’ attitudes to self-care. “It is hard and sometimes feels selfish to set aside “me time” but it matters so much,” she says. “It is probably the hardest and most important part of being a carer.”

Carers prioritise the needs of those they are caring for and if this means giving up work, the cost to the carer can be personal as well as financial. Another Carers Trust case study, ‘Claire’s story’, makes this point. When her mum was first diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, Claire gave up work for about a year and a half to look after her. “Having someone with her all day was really beneficial for her, however, it was difficult for me as I felt like I had lost my identity,” she says. “I had become just a ‘carer’ which was a hard adjustment to make.”

Claire now works four days a week, but it may not be possible for other carers to achieve this balance.

The benefits system

For some carers, benefits provide a financial lifeline and those who already receive state benefits can receive an additional £38.85 a week carer premium. But the rules around the Carer’s Allowance – the main benefit carers can claim – are far from perfect.

Carer’s Allowance is currently £69.70 a week but to qualify carers need to spend over 35 hours a week caring for someone who receives certain benefits for their illness or disability. If the carer works, they will only get Carer’s Allowance if they earn £132 or less a week after tax, National Insurance and expenses such as half their pension contributions.

Carers who are in full-time education or studying more than 21 hours a week do not qualify for Carer’s Allowance and people who are caring for more than one person are not paid extra. These rules can force people to choose between caring or continuing in paid work or education.

Another problem is that people who become carers after state pension age can’t be paid Carer’s Allowance plus their state pension, as both are intended to replace lost income and duplication of benefits is not allowed.

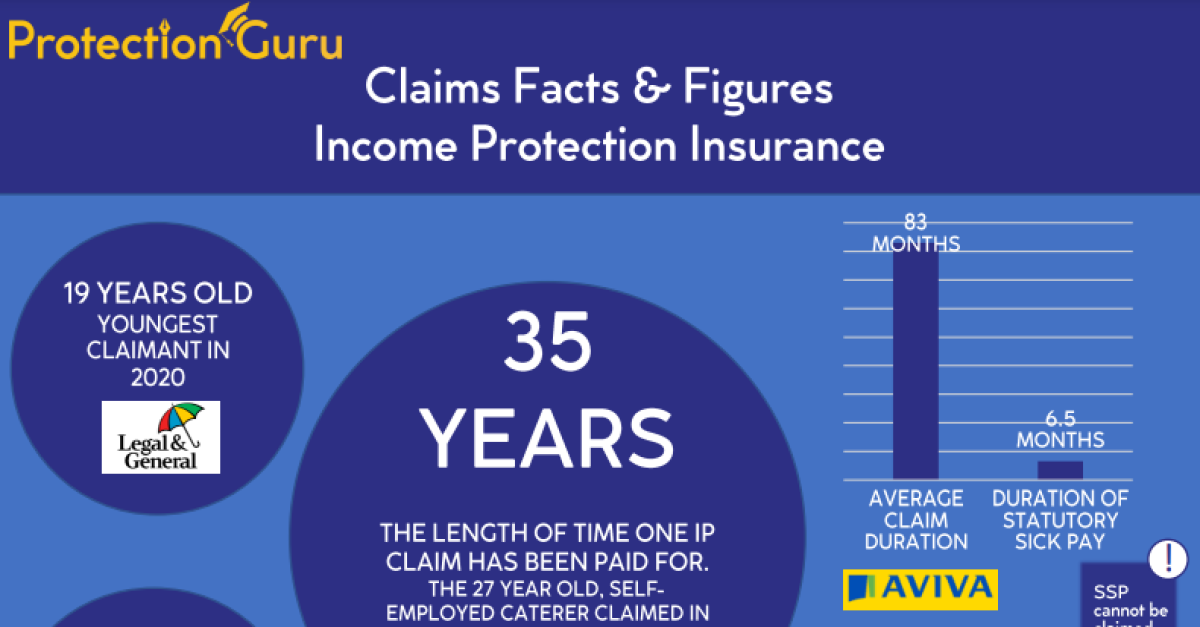

Given the financial struggles many carers face due to their reduced capacity to work, advisers may want to make clients aware that some income protection providers – AIG, British Friendly and Zurich – provide financial support if the policy holder’s direct family develops a care need.

Things to reflect on for CPD:

- What are the your three learning points from this article. Reflect on how caring for for family, friends or neighbours who are ill can impact your clients lives and the benefits available?

- Required further reading: What support is availble to carers through income protection insurance?

- Carers often describe their role as rewarding, but it can be tough personally and financially. Read this insight to see how protection plans help clients manage their mental wellbeing.